Contents

Caulerpa taxifolia is a species of green seaweed, an alga of the genus Caulerpa, native to tropical waters of the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, and Caribbean Sea.[2] The species name taxifolia arises from the resemblance of its leaf-like fronds[3] to those of the yew (Taxus). [citation needed]

A strain of the species bred for use in aquariums has established non-native populations in waters of the Mediterranean Sea, the United States, and Australia.[4] It is one of two species of algae listed in 100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species compiled by the IUCN Invasive Species Specialist Group.[5]

Description

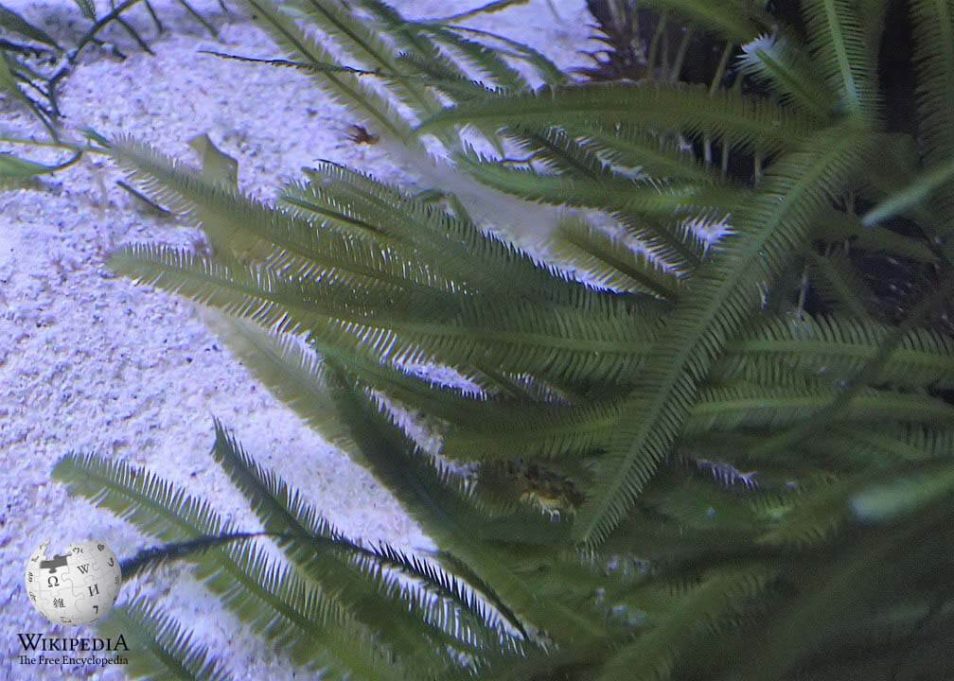

C. taxifolia is light green[3] with stolons (stems) on the sea floor, from which sparsely-branched upright fronds of approximately 20–60 cm (8–24 in) in height arise.[6] Algae in the genus Caulerpa synthesize a mixture of toxins[7] termed , believed to impart a peppery taste to the plants.[8] The effects of the specific toxin synthesized by C. taxifolia, , have been studied,[9][10] with extracts from C. taxifolia being found to negatively affect P-glycoprotein-ATPase in the sea sponge G. cydonium.[11]

Like all members of the genus Caulerpa, C. taxifolia consists of a single cell with many nuclei. The algae has been identified as the largest known single-celled organism.[12] Wild-type C. taxifolia is monoecious.[13]

Use in aquaria

Caulerpa species are commonly used in aquaria for their aesthetic qualities and ability to control the growth of undesired species.[14] C. taxifolia has been cultivated for use in aquaria in western Europe since the early 1970s.[15] A clone of the alga that was resistant to cold was observed in the tropical aquarium at the Wilhelma Zoo in Stuttgart[16] and further bred by exposure to chemicals and ultraviolet light.[17] The zoo distributed the strain to other aquaria, including the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco.[16]

The aquarium strain is morphologically identical to native populations of the species.[3] However, a 2008 study found that a population of the aquarium strain near Caloundra, Australia exhibited markedly reduced sexual reproduction, with only male plants present during some reproductive episodes.[13] The aquarium strain can survive out of water for up to 10 days in moist conditions, with 1 cm fragments capable of producing viable plants.[18]

Status as invasive species

Outside its native range, C. taxifolia is listed as an invasive species.[19][20] It is one of two algae on the list of the world's 100 worst invasive species compiled by the IUCN Invasive Species Specialist Group (alongside Wakame).[5] The species is able to thrive in heavily polluted waters,[21] possibly contributing to its spread in the Mediterranean.[22]

Presence in the Mediterranean Sea

The presence of C. taxifolia in the Mediterranean was first reported in 1984[23] in an area adjacent to the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco.[24] Alexandre Meinesz, a marine biologist, attempted to alert Moroccan and French authorities to the spread of the strain in 1989,[16] but the governments failed to respond to his concerns.[25] The occurrence of the strain is generally believed to be due to an accidental release by the museum,[3][26] but Monaco rejected the attribution and instead claimed that the observed algae was a mutant strain of C. mexicana.[25] By 1999, scientists agreed that it was no longer possible to eliminate the presence of C. taxifolia in the Mediterranean.[25]

A study published in 2002 found that beds of Posidonia oceanica in the Bay of Menton were not negatively affected eight years after colonization by C. taxifolia.[27] Other published studies have shown that fish diversity and biomass are equal or greater in Caulerpa meadows than in seagrass beds[28] and that Caulerpa had no effect on composition or richness of fish species.[29]

Studies in 1998[15] and 2001[23] found that the strain observed in the Mediterranean was genetically identical to aquarium strains, with similarities to an additional population in Australia.

Presence in Australia

A 2007 study found that a native bivalve mollusc species was negatively affected by the presence of C. taxifolia, but that the effect was not necessarily different from that of native seagrass species.[30] A 2010 study indicated that the effect of detritus from C. taxifolia negatively impacted abundance and species richness.[31]

Presence in California

C. taxifolia was found in waters near San Diego, California, in 2000,[32] where chlorine bleach was used in efforts to eradicate the strain.[33] The strain was declared eradicated from Agua Hedionda Lagoon in 2006.[34] California passed a law in 2001 forbidding the possession, sale, transport, or release of Caulerpa taxifolia within the state.[35] The Mediterranean clone of C. taxifolia was listed as a noxious weed in 1999[36] by the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, prohibiting interstate sale and transport of the strain without a permit under the Noxious Weed Act and Plant Protection Act.[24][37]

Other negative effects

C. taxifolia may become entangled in fishing gear and boat propellers.[4]

Control methods

C. taxifolia may be controlled via mechanical removal, poisoning with chlorine, or application of salt.[6] Researchers at the University of Nice investigated possible use of a species of sea slug, Elysia subornata, as a possible natural control method, but found that it was not suitable for use in the Mediterranean due to cold winter water temperatures and insufficient population density.[38]

Gallery

-

C. taxifolia on display at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo, Japan

-

A field of C. taxifolia amongst seagrass

-

A Pacific cleaner shrimp (Lysmata amboinensis) on top of a C. taxifolia specimen within a marine aquarium

See also

References

- ^ Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. (2007). "Genus: Caulerpa taxonomy browser". AlgaeBase version 4.2 World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- ^ "Macroalga Killer Algae; Aquarium-Mediterranean Strain: Caulerpa taxifloria" (PDF). Dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ a b c d "GISD". Invasive Species Specialist Group. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ a b "Aquarium Aulerpa". Marine Biosecurity Porthole. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ a b "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species". Global Invasive Species Database (International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved Jan 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "Aquarium Caulerpa". Weeds Australia - Profiles. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Nielsen, Peter G.; Carlé, Jørgen S.; Christophersen, Carsten (January 1982). "Final structure of caulerpicin, a toxin mixture from the green alga Caulerpa racemosa". Phytochemistry. 21 (7): 1643–1645. Bibcode:1982PChem..21.1643N. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(82)85032-2.

- ^ Doty, Maxwell S.; Aguilar-Santos, Gertrudes (August 1966). "Caulerpicin, a Toxic Constituent of Caulerpa". Nature. 211 (5052): 990. Bibcode:1966Natur.211..990D. doi:10.1038/211990a0. PMID 5968321. S2CID 4214966.

- ^ Pesando, Danielle; Lemée, Rodolphe; Ferrua, Corine; Amade, Philippe; Girard, Jean-Pierre (October 1996). "Effects of caulerpenyne, the major toxin from Caulerpa taxifolia on mechanisms related to sea urchin egg cleavage". Aquatic Toxicology. 35 (3–4): 139–155. Bibcode:1996AqTox..35..139P. doi:10.1016/0166-445X(96)00013-6.

- ^ Mozzachiodi, R; Scuri, R; Roberto, M; Brunelli, M (November 2001). "Caulerpenyne, a toxin from the seaweed Caulerpa taxifolia, depresses afterhyperpolarization in invertebrate neurons". Neuroscience. 107 (3): 519–526. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00365-7. PMID 11719006. S2CID 40312176.

- ^ Müller, Werner E.G.; Koziol, Claudia; Wiens, Matthias; Schröder, Heinz C. (2000). "Stress Response in Marine Sponges: Genes and Molecules Involved and Their use as Biomarkers". Environmental Stressors and Gene Responses. Cell and Molecular Response to Stress. Vol. 1. pp. 193–208. doi:10.1016/S1568-1254(00)80016-9. ISBN 978-0-444-50488-3.

- ^ Ranjan, Aashish; Townsley, Brad T.; Ichihashi, Yasunori; Sinha, Neelima R.; Chitwood, Daniel H. (8 January 2015). "An Intracellular Transcriptomic Atlas of the Giant Coenocyte Caulerpa taxifolia". PLOS Genetics. 11 (1) e1004900. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004900. PMC 4287348. PMID 25569326.

- ^ a b Phillips, Julie A. (February 2009). "Reproductive ecology of Caulerpa taxifolia (Caulerpaceae, Bryopsidales) in subtropical eastern Australia". European Journal of Phycology. 44 (1): 81–88. Bibcode:2009EJPhy..44...81P. doi:10.1080/09670260802343640. S2CID 84880590.

- ^ "A closer look at Caulerpa - common aquarium species and their care". Conscientious Aquarist Magazine. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ a b Jousson, O.; Pawlowski, J.; Zaninetti, L.; Meinesz, A.; Boudouresque, C. F. (22 October 1998). "Molecular evidence for the aquarium origin of the green alga Caulerpa taxifolia introduced to the Mediterranean Sea". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 172: 275–280. Bibcode:1998MEPS..172..275J. doi:10.3354/meps172275.

- ^ a b c "Chronology of an Invasion". NOVA. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Pierre Madl; Maricela Yip (2004). "Literature Review of Caulerpa taxifolia". BUFUS-Info. 19 (31). Archived from the original on 2022-10-08. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Caulerpa Taxifolia or Killer Alga". Center for Invasive Species Research. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Schaffelke, Britta (2008). "Caulerpa taxifolia". Invasive Species Compendium (CABI International). CABI Compendium 29292. doi:10.1079/cabicompendium.29292. Archived from the original on 2017-07-23. Retrieved Jan 24, 2021.

- ^ "Caulerpa taxifolia". Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants (University of Florida). Archived from the original on 2017-08-06. Retrieved Jan 24, 2021.

- ^ "Introduced Species Summary Project Killer Algae (Caulerpa taxifolia)". columbia.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Houngnandan, Fabrice; Kefi, Sonia; Deter, Julie (October 2021). "The joint influence of environmental and anthropogenic factors on the invasion of two alien caulerpae in northwestern Mediterranean". Biological Invasions. 24 (2): 449–462. doi:10.1007/s10530-021-02654-w.

- ^ a b Wiedenmann, J.; Baumstark, A.; Pillen, T. L.; Meinesz, A.; Vogel, W. (19 February 2001). "DNA fingerprints of Caulerpa taxifolia provide evidence for the introduction of an aquarium strain into the Mediterranean Sea and its close relationship to an Australian population". Marine Biology. 138 (2): 229–234. Bibcode:2001MarBi.138..229W. doi:10.1007/s002270000456. S2CID 84150417.

- ^ a b "Aquatic Invasive Species on the West Coast". NOAA Fisheries. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ a b c "Fifteen years ago it was a small patch of seaweed, now it threatens to ruin the Mediterranean coast". The Guardian. 3 August 1999. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Schaffelke, Britta (2008). "Caulerpa taxifolia". Invasive Species Compendium. CABI Compendium 29292. doi:10.1079/cabicompendium.29292. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Jaubert, Jean M.; Chisholm, John R. M.; Ducrot, Danielle; Ripley, Herb T.; Roy, Laura; Passeron-Seitre, Gilles (December 1999). "No deleterious alterations in Posidonia beds in the Bay of Menton (France) eight years after Caulerpa taxifolia colonization". Journal of Phycology. 35 (6): 1113–1119. Bibcode:1999JPcgy..35.1113J. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.1999.3561113.x. S2CID 85127610.

- ^ Relini, G., M Relini, and G. Torchia. (1998) Fish biodiversity in a Caulerpa taxifolia meadow in the Ligurian Sea. Italian Journal of Zoology 65 Supplement:465-470.

- ^ Francour, P.; Harmelin-Vivien, M.; Harmelin, J. G.; Duclerc, J. (1 March 1995). "Impact of Caulerpa taxifolia colonization on the littoral ichthyofauna of North-Western Mediterranean sea: preliminary results". Hydrobiologia. 300 (1): 345–353. Bibcode:1995HyBio.300..345F. doi:10.1007/BF00024475. S2CID 23445784.

- ^ Wright, Jeffrey T.; McKenzie, Louise A.; Gribben, Paul E. (2007). "A decline in the abundance and condition of a native bivalve associated with Caulerpa taxifolia invasion". Marine and Freshwater Research. 58 (3): 263. Bibcode:2007MFRes..58..263W. doi:10.1071/MF06150.

- ^ Taylor, Skye L.; Bishop, Melanie J.; Kelaher, Brendan P.; Glasby, Tim M. (16 December 2010). "Impacts of detritus from the invasive alga Caulerpa taxifolia on a soft sediment community". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 420: 73–81. Bibcode:2010MEPS..420...73T. doi:10.3354/meps08903.

- ^ "Killer Algae Invades Southern Cal". Wired. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Williams, Sl; Schroeder, Sl (2004). "Eradication of the invasive seaweed Caulerpa taxifolia by chlorine bleach". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 272: 69–76. Bibcode:2004MEPS..272...69W. doi:10.3354/meps272069.

- ^ "Agua Hedionda Caulerpa Taxifolia Eradication Program". Southern California Wetlands Recovery Project. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ "Assembly Bill No. 1334, Chapter 338". California Legislative Information. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ "Noxious Weeds; Notice of Availability of Petitions To Regulate Caulerpa". Federal Register. 26 October 2004. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ "Noxious Weed Regulations" (PDF). govinfo.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Thibaut, Thierry; Meinesz, Alexandre; Amade, Philippe; Charrier, Stéphane; De Angelis, Kate; Ierardi, Santina; Mangialajo, Luisa; Melnick, Jennifer; Vidal, Valérie (June 2001). "Elysia subornata (Mollusca) a potential control agent of the alga Caulerpa taxifolia (Chlorophyta) in the Mediterranean Sea". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 81 (3): 497–504. Bibcode:2001JMBUK..81..497T. doi:10.1017/S0025315401004143. S2CID 85066136.

Further reading

- Peplow, Mark (23 March 2005). "Algae create glue to repair cell damage". Nature: news050321–11. doi:10.1038/news050321-11.

- LaMonica, Martin (20 May 2005). "Start-up drills for oil in algae". CNET.

- Theodoropoulos, David. 2003. Invasion Biology: Critique of a Pseudoscience. pages 42,159. Avvar Books, Blythe, CA. 237 p. ISBN 0-9708504-1-7

External links

- Attack of the killer algae - Eric Noel Muñoz on YouTube

- Killer Algae, 2001 BBC Documentary

- In-depth article on invasions of Caulerpa taxifolia, source as escaped aquarium plant, etc.

- Caulerpa Taxifolia fact sheet Archived 2022-10-08 at the Wayback Machine

- An excerpt from Killer Algae by Alexandre Meinesz

- Caulerpa taxifolia at the Center for Invasive Species Research

- "Deep Sea Invasion" Nova (TV series) broadcast April 1, 2003

- Species Profile- Caulerpa, Mediterranean Clone (Caulerpa taxifolia), National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library. Lists general information and resources for Caulerpa, Mediterranean Clone.