Contents

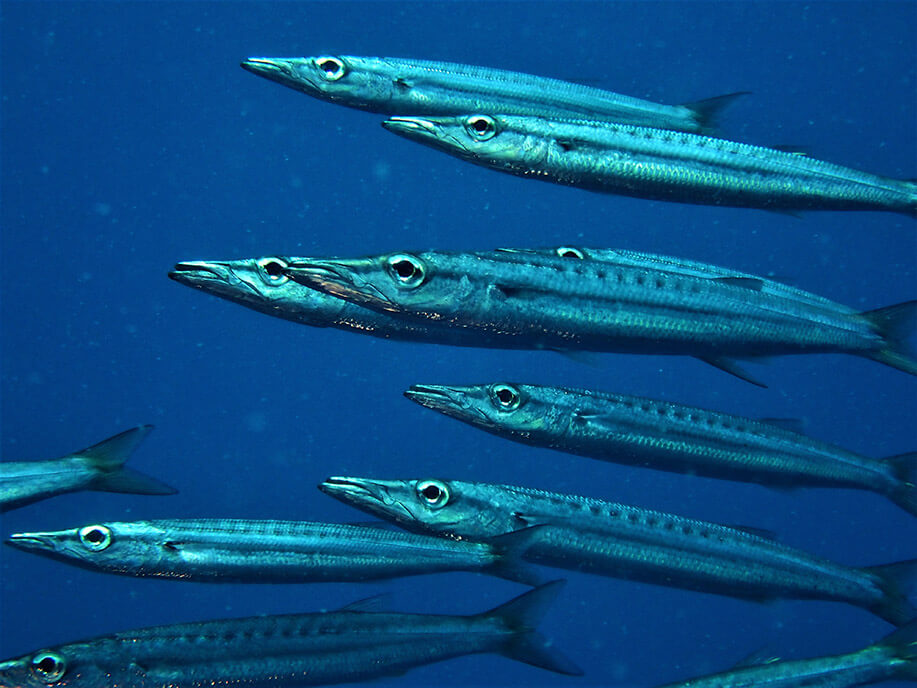

The blackfin barracuda (Sphyraena qenie), also known as the chevron barracuda, is known for its aggressive, predatory personality.[1]

Distribution

This species of barracuda ranges from the Red Sea and East Africa to the Indo and Western Pacific and as far as French Polynesia and typically live in tropical and temperate waters.[2] The Indo-Pacific Ocean has tropical and subtropical waters that make it a favorable habitat for S. qenie.[2] The first sighting of this species in Indian waters was in 1966.[1]

Although rare, this species can also be found in the tropical East Pacific.[2][3]

In Japan, they can be found in the waters around Ryukyu, Amami Oshima, Yonaguni, Tanega, and Ishigaki Islands.[2] For Ryukyu Island, only the adults migrate there from tropical waters when temperatures are too high.[2] Additionally, during the summer seasons, they have also been spotted near Okinoerabu Island waters from July to October.[2]

Habitat

It is typically encountered on coral reefs down to 50 m (160 ft) where it forms large schools.[4][5][6][7] During the hours of late afternoon through dusk, S. qenie leaves the reefs to feed, going to relatively deep waters to find its prey.[3][8]

Description

The blackfin barracuda reaches a maximum size of 140 cm (55 in). The blackfin barracuda is known for its long black lateral bands that go around its body. These bands extend laterally down the torso and are v-shaped with the apex facing to the front.[1] There are about 18 to 22 bands that are on the fish's body. The number of bands sets them apart from similar species, the S. jello and S. putnamae.[8]

It has elongated last rays on the second dorsal fin and anal fins and a blackish caudal fin.[citation needed]

One of the most distinct features of this species of barracuda is that they lack gill rakers.[1][2][8]

As for their mouths, the maxilla, or upper jaw, goes in a vertical line through the front of their eyes and the lower jaw, which is longer than the upper jaw.[1] This upper jaw has a conical tip that is distinct to this species.[1] Next to the mouth, their preopercle does not have a skinny flap, as most others do.[1]

The anal fin is located in the middle under the second dorsal fin, and the heart is located near the anal.[1]

Although this species is very similar to S. putnamae, there are some differences that set it apart. S. qenie has 19 or 20 longitudinal scale rows that are level with the middle and ventral margins of the eye[2] while S. putnamae has 11-15. As for the scales extending between the eye and preopercular margin[2] S. qenie has 25-27, and S. putnamae has 15-20.[2] Additionally, the upper jaw of S. qenie is shorter, allowing for the distinct longer bottom jaw, the first dorsal and pelvis fins are towards the front of the body, and the anal fin and second dorsal have longer anterior rays.[2] It also has a slimmer body insertion.[2]

Originally, S. qenie was thought to be a smaller version of Sphraena nigripinnis but scientists later found that the caudal fins of S. nigripinnis are relatively forked, and they also have two well-developed lobes that are very large.[8]

Human use

S. qenie is not a favorable sport fish, but is used for forms of longline fishing. Its delicate flesh is flavorful, making it desirable as bait, especially for catching tuna.[1][9] It is usually caught at night by trawling,[3][9] but for this reason, is not commonly spotted in American Samoa.[9]

In a study conducted in remote Oceania to find levels of Mercury (Hg) in coral reef systems, S. qenie played an important role in indicating the amounts of Hg in remote ecosystems.[9] It was found that by world health standards, levels of Mercury were high in reef predators that live in the waters that weren't impacted and that eating these top-trophic reef fish might have to be warranted at the time.[9]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dutt, S.; Seshagiri Rao, B. V. (1967-06-01). "The sphyraenidae of the Indian coasts". Proceedings / Indian Academy of Sciences. 65 (6): 238–248. doi:10.1007/BF03052548. ISSN 0370-0097.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Morishita, Satoshi; Miki, Ryohei; Wada, Hidetoshi; Itou, Masahide; Motomura, Hiroyuki (2020-07-01). "Morphological comparisons of Sphyraena qenie with S. putnamae, with a revised key to Indo-Pacific species of Sphyraena lacking gill rakers (Sphyraenidae)". Ichthyological Research. 67 (3): 456–463. Bibcode:2020IchtR..67..456M. doi:10.1007/s10228-020-00738-6. ISSN 1616-3915.

- ^ a b c Bearez, Philippe (March 2008). "Occurrence of Sphyraena qenie (Sphyraenidae) in the tropical eastern Pacific, with a key to the species of barracudas occurring in the area". Cybium. 32 (1): 95–96.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Sphyraena qenie". FishBase. February 2014 version.

- ^ WoRMS. "Sphyraena qenie Klunzinger, 1870". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Lieske, Ewald; Myers, Robert (2004). Coral reef guide. Red Sea. HarperCollins. p. 207. ISBN 9780007741731.

- ^ Allen, Gerald; Erdmann, Mark (2013). Reef Fishes of the East Indies - Volume III.

- ^ a b c d Miki, Ryohei; Hata, Harutaka; Motomura, Hiroyuki (2019). "Records of the Barracuda Sphyraena qenie from Japan, with Notes on the Taxonomic Status of Sphyraena nigripinnis (Teleostei: Sphyraenidae)". Species Diversity. 24 (1): 23–27. doi:10.12782/specdiv.24.23.

- ^ a b c d e Morrison, John; Peshut, Peter; West, Ronald; Lasorsa, Brenda (28 May 2015). "Mercury (Hg) speciation in coral reef systems of remote Oceania: Implications for the artisanal fisheries of Tutuila, Samoa Islands". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 96 (1–2): 41–56. Bibcode:2015MarPB..96...41M. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.05.049. PMID 26028166. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

External links

- Photos of Blackfin barracuda in the Sealife Collection