Contents

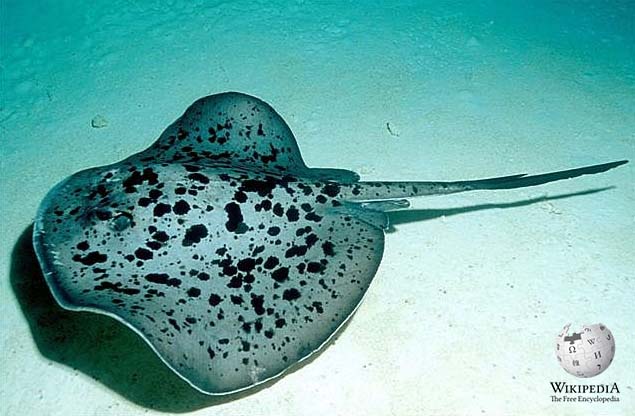

The round ribbontail ray or blotched fantail ray,[1] (Taeniurops meyeni) is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, found throughout the nearshore waters of the tropical Indo-Pacific, as well as off islands in the eastern Pacific. It is a bottom-dwelling inhabitant of lagoons, estuaries, and reefs, generally at a depth of 20–60 m (66–197 ft). Reaching 1.8 m (5.9 ft) across, this large ray is characterized by a thick, rounded pectoral fin disc covered by small tubercles on top, and a relatively short tail bearing a deep ventral fin fold. In addition, it has a variable but distinctive light and dark mottled pattern on its upper surface, and a black tail.

Generally nocturnal, the round ribbontail ray can be solitary or gregarious, and is an active predator of small, benthic molluscs, crustaceans, and bony fishes. It is aplacental viviparous, with the embryos sustained by yolk, and later histotroph ("uterine milk") secreted by the mother; up to seven pups are born at a time. Although not aggressive, if provoked the round ribbontail ray will defend itself with its venomous tail spine, and it has been responsible for at least one fatality. It is valued by ecotourist divers and recreational anglers. This slow-reproducing species is threatened by commercial fishing, both targeted and bycatch, and habitat degradation across much of its range. As a result, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed it as Vulnerable.[1]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

As Taeniurops meyeni, the round ribbontail ray was described by German biologists Johannes Peter Müller and Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle in their 1841 Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen, based on two syntypes collected from Mauritius. However, this species is better known under the name Taeniura melanospilos, which was applied by Dutch ichthyologist Pieter Bleeker to a juvenile specimen from Java, in a 1953 volume of the scientific journal Natuurkundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië.[2][3]

Other common names for the round ribbontail ray include black spotted ray, black-blotched stingray, black-spotted stingray, fantail ray, fantail stingray, giant reef ray and speckled stingray.[4] In Australia, it is one of several species referred to as "bull ray".[5] A minority of authors place this species with the river stingrays in the family Potamotrygonidae.[1] Preliminary morphological examination has suggested that the round ribbontail ray is more related to Dasyatis and Indo-Pacific Himantura than to the congeneric bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma), which is closer to the amphi-American Styracura (S. pacifica and S. schmardae) and the river stingrays.[6]

Etymology

The ray is named in honor of Franz Julius Ferdinand Meyen (1804–1840), a physician and a botanist, who collected or supplied the type specimens.[7]

Description

The round ribbontail ray has a thick pectoral fin disc wider than it is long, with a smoothly rounded outer margin. The eyes are of medium size and are followed by larger spiracles. There is a short and broad curtain of skin between the oval nostrils, with a finely fringed trailing margin. The mouth is wide and curved, with faint furrows at the corners. There is a row of seven papillae on the floor, with the outermost pair smaller and set apart from the others.[8] There are 37–46 tooth rows in the upper jaw and 39–45 tooth rows in the lower jaw.[9] The teeth are small with a deep groove across the crown and are arranged in a dense quincunx pattern into flattened surfaces.[10]

The pelvic fins are small and narrow.[8] The tail is relatively short, not exceeding the width of the disc, and bears one (rarely two) long, serrated stinging spine on the upper surface. The base of the tail is broad; past the spine, the tail rapidly thins, and bears a deep ventral fin fold that runs to the tail tip.[8] The upper surface of the disc and tail are roughened by a uniform covering of small, widely spaced granules. There is also a midline row of sharp tubercles on the back, with two shorter rows alongside. The first of these tubercles develop at a length of around 46 cm (18 in), over the "shoulders" and in the single midline row.[10]

The dorsal coloration is light to dark gray, brown-gray, or purplish, becoming most intense towards the fin margins, with a highly variable pattern of irregular darker mottling and white speckles or streaks. The tail past the spine, including the fin fold, is uniformly black, while the underside is creamy-white with darker fin margins and additional dots. Young rays are more plain in coloration than adults.[10][11] One of the largest stingray species, the round ribbontail ray can grow to 1.8 m (5.9 ft) across, 3.3 m (11 ft) long, and 150 kg (330 lb) in weight.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The round ribbontail ray has a wide distribution in the Indo-Pacific region: it is found from KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa northward along the East African coast to the Red Sea, including Madagascar and the Mascarenes; from there, its range extends eastward through the Indian subcontinent to Southeast Asia and Micronesia, occurring as far north as Korea and southern Japan, and as far south as Australia, where it is found from at least Ningaloo Reef off Western Australia to Stradbroke Island off Queensland, including Lord Howe Island.[8] In the easternmost portion of its range, it has been reported from Cocos Island and the Galápagos Islands, with individuals possibly dispersing as far as Central America.[4]

Bottom-dwelling in nature, the round ribbontail ray is typically found close to shore at a depth of 20–60 m (66–197 ft), though it has been reported anywhere from the surf zone to a depth of 439 m (1,440 ft).[1][4] It favors sand or rubble bottoms in shallow lagoons or near coral and rocky reefs, and may also enter estuaries.[10][12]

Biology and ecology

The round ribbontail ray has nocturnal habits and rests motionless for much of the day, often near vertical structures, in caves, or under ledges.[11] It may be solitary, or form small to large groups. This ray is frequently shadowed by one or more jacks or cobia (Rachycentron canadum); these smaller fishes may feed on food stirred up by the ray's activities, or use the ray's body as cover for approaching their own prey.[12] The round ribbontail ray hunts for bivalves, crabs, shrimps, and small bony fishes on the bottom.[11] When feeding, it adopts a characteristic posture in which it presses the margin of its disc against the bottom and takes in water through its spiracles, which it blows through its mouth to uncover prey buried in the sediment.[13] This species may fall prey to larger fishes such as sharks, and marine mammals.[3] When threatened, it raises its tail over its back so that the spine faces forward, and waves it back and forth.[11] Known parasites of this species include the monogenean ,[14] ,[15] and ,[16] and the nematode .[17]

Little information is available on the life history of the round ribbontail ray. Like other stingrays, it is aplacental viviparous: the unborn embryos are initially sustained by yolk, which is later supplemented by histotroph ("uterine milk", containing proteins, lipids, and mucus) produced by the mother.[3] Reproductive aggregations numbering in the hundreds have been observed at Cocos Island shortly after the onset of La Niña, which brings cooler temperatures. During these periods a single female may be pursued by dozens of males.[13] Females bear litters of up to seven pups, each measuring 33–35 cm (13–14 in) across and 67 cm (26 in) long.[1] Off South Africa, birthing may take place in the summer.[18] Males attain sexual maturity at a disc width of 1.0–1.1 m (3.3–3.6 ft); the maturation size of females is unknown.[1]

Human interactions

The round ribbontail ray is not aggressive and has been known to approach and investigate divers.[10] However, if harassed it can inflict a severe wound with its venomous tail spine. This species has been responsible for at least one recorded fatality of a diver who was stabbed while attempting to ride the ray. The round ribbontail ray is popular with ecotourist divers because of its size and spectacular appearance.[1][11]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the round ribbontail ray as Vulnerable. It cannot withstand heavy fishing pressure due to its low reproductive rate, and there is widespread degradation of its coral reef habitat, including from agricultural runoff and destructive fishing practices such as blast fishing. This species is caught by commercial and fisheries throughout its range, using line gear and trawls. One region where it is heavily pressured is in Indonesian waters, where it and other large rays are taken intentionally and otherwise by tangle netters, longliners, and trawlers operating off Java, Bali, New Guinea, and Lombok. All landed individuals are brought to market for human consumption.[1]

Off South Africa, the round ribbontail ray is captured incidentally by prawn trawlers on offshore banks, but is not utilized. Because of its size and strength, it is also prized by sport anglers, who usually release it unharmed. South Africa sets a recreational bag limit of one ray per species per person per day and does not allow spearfishing for this species.[1][18] In Australian waters, this ray has been assessed as of Least Concern. Although it is caught (and discarded) by prawn trawlers, this mortality has been reduced by the mandatory installation of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs). Furthermore, a portion of its Australian range lies within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. This species has also been listed under Least Concern in the Maldives where, due to the tourist value of rays, the government has created protected marine reserves and banned the export of rays in 1995 and ray skins in 1996.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sherman, C.S.; Bennett, R.; Charles, R.; Haque, A.B.; Jabado, R.W.; Simpfendorfer, C.; Van Beuningen, D. (2024). "Taeniurops meyeni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2024 e.T60162A124445924. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard, eds. (February 19, 2010). "Species related to Taeniurops meyeni". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Bester, C. "Biological Profiles: Blotched Fantail Ray". Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Taeniura meyeni". FishBase. February 2010 version.

- ^ Bull ray, stingray spines Archived 2006-08-21 at the Wayback Machine. Julian Rocks. Retrieved on February 25, 2010.

- ^ Lovejoy, N.R. (1996). "Systematics of myliobatoid elasmobranchs: with emphasis on the phylogeny and historical biogeography of neotropical freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygonidae: Rajiformes)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 117 (3): 207–257. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1996.tb02189.x.

- ^ Christopher Scharpf & Kenneth J. Lazara (22 September 2018). "Order MYLIOBATIFORMES (Stingrays)". The ETYFish Project Fish Name Etymology Database. Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Last, P.R. & J.D. Stevens (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 460–461. ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2.

- ^ Smith, J.L.B.; M.M. Smith & P.C. Heemstra (2003). Smiths' Sea Fishes. Struik. p. 141. ISBN 1-86872-890-0.

- ^ a b c d e Grove, J.S. & R.J. Lavenberg (1997). The Fishes of the Galápagos Islands. Stanford University Press. pp. 119–121. ISBN 0-8047-2289-7.

- ^ a b c d e Ferrari, A. & Ferrari, A. (2002). Sharks. FireFly Books. pp. 212–213. ISBN 1-55209-629-7.

- ^ a b Michael, S.W. (1993). Reef Sharks & Rays of the World. Sea Challengers. p. 89. ISBN 0-930118-18-9.

- ^ a b Hennemann, R.M. (2001). Sharks & Rays: Elasmobranch Guide of the World (second ed.). IKAN – Unterwasserarchiv. pp. 256–259. ISBN 3-925919-33-3.

- ^ Timofeeva, T.A. (1983). "New representatives of monocotylids (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from cartilaginous fishes of the South China and Yellow Seas". Trudy Zoologicheskogo Instituta. 121: 35–47.

- ^ Chisholm, L.A. & I.D. Whittington (March 2004). "Two new species of Dendromonocotyle Hargis, 1955 (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from the skin of Taeniura meyeni (Dasyatidae) and Aetobatus narinari (Myliobatidae) from aquaria in Queensland, Australia". Systematic Parasitology. 57 (3): 221–228. doi:10.1023/B:SYPA.0000019085.44664.6d. PMID 15010596. S2CID 34868807.

- ^ Whittington, I.D. & G.C. Kearn (2009). "Two new species of entobdelline skin parasites (Monogenea, Capsalidae) from the blotched fantail ray, Taeniura meyeni, in the Pacific Ocean, with comments on spermatophores and the male copulatory apparatus" (PDF). Acta Parasitologica. 54 (1): 12–21. doi:10.2478/s11686-009-0013-7. S2CID 28685675.

- ^ Deardorff, T.L. & R.C. Ko (1983). "Echinocephalus overstreeti sp. N (Nematoda, Gnathostomatidae) in the stingray, Taeniura melanospilos Bleeker, from the Marquesas Islands, with comments on E. sinensis Ko 1975". Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington. 50 (2): 285–293.

- ^ a b Van der Elst, R. (1993). A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa (third ed.). Struik. p. 53. ISBN 1-86825-394-5.

External links

- Fishes of Australia : Taeniura meyeni

- Photos of Round ribbontail ray in the Sealife Collection